The end of the transatlantic trade consensus?

Trump, Brexit and European scepticism about TTIP spell the end of transatlantic leadership on trade. With America looking inward, and Britain absorbed by Brexit, the EU must act to avoid the collapse of the liberal economic order.

It is easy to blame Donald Trump for the stalled talks on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). Trump’s scepticism about free trade has been on open display ever since he decided to run for the US presidency. One of his first acts after his inauguration was to withdraw the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade pact with 11 Pacific states negotiated by his predecessor, and announce that he would renegotiate parts of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the United States, Mexico and Canada.

Trump’s objective is to increase US employment and boost the economy, raising new trade barriers in the process. He has threatened punitive tariffs on companies that outsource US jobs, is seeking to force them to repatriate profits and has suggested raising tariffs on Mexican and Chinese imports. He may also adopt a border tax that would impose a levy on corporate imports and exempt export revenues from taxation. The latter measure could fall foul of non-discrimination rules in the World Trade Organisation (WTO). He has hinted that if the WTO takes action against America, he might respond by pulling the US out of this fundamental institution of the liberal rules-based trading order. The ‘Trump doctrine’ sees trade surpluses as good, trade deficits as bad, and trade agreements as zero-sum, transactional deals. Team Trump thinks it is better to leverage US economic muscle in bilateral talks than entangle the country in a multilateral system of trade partnerships.

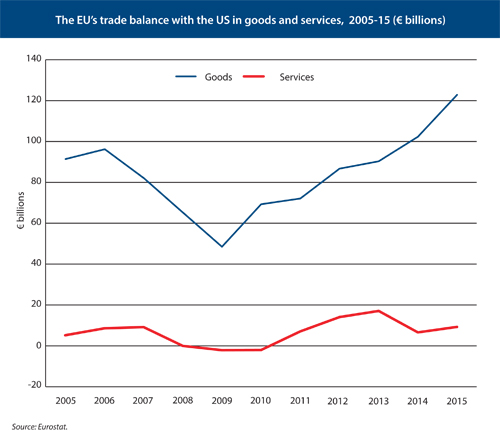

Though he has not explicitly pulled the US out of the TTIP talks, Trump’s economic nationalism dims the prospects for a transatlantic trade deal. It does not help that he has been explicitly hostile to the EU. The US has a substantial trade deficit with the EU, which won’t please Trump: it was €122 billion in goods and €9 billion in services in 2015. Since the EU and the US are almost equal-sized economies, Trump also knows the US would not be negotiating as the senior partner. He has described the EU as “the consortium” and a “vehicle for Germany”, claimed that it “was formed, partially, to beat the United States on trade” and said that it would not matter if the EU split apart. Peter Navarro, one of his top trade advisors, recently accused Berlin of being a currency manipulator. In a letter to EU heads of state in January, Donald Tusk, the president of the EU Council, wrote that Trump’s comments, along with an assertive China, Russian aggression and instability and terrorism in the Middle East, were part of a patchwork of foreign threats facing the club.

#Trump wants to leverage US econ muscle in bilateral deals, not entangle the US in multilateral ones

The likely demise of TTIP is another blow to the global trading order. As well as reducing tariffs and deepening market access, TTIP was designed to allow the United States and the EU to reassert their leadership role in trade policy, setting global rules and norms on issues like labour and environmental standards, and on investment protection. The size of their combined markets would oblige other trading countries to adopt the same, higher standards, thus helping create a level playing field.

Rulemaking is most effective and least disruptive when done at the multilateral level. But the WTO Doha round failed. TTIP and TPP emerged as second-best options to remove trade barriers and set standards among major trading partners in Asia, the US and Europe. There was also a clear strategic rationale for these deals. They would enable the transatlantic partners and like-minded Asian countries to set the direction of global trade policy, making it more difficult for countries like China, Russia and others to undermine the open, rules-based trading order through protectionist and illiberal practices. In October 2015, Barack Obama warned that without TPP, “competitors that don't share our values, like China, will write the rules of the global economy”. Now, Trump appears enamoured of the kind of policies Washington has traditionally castigated emerging economies for touting. The international trade system will probably become more messy, more bilateral and more protectionist.

European politicians have plenty of reasons to be wary of Trump. But TTIP had ground to a halt well before he was elected. The talks lost momentum after the British voted to leave the EU in June. In August, senior cabinet members in the German and French governments publicly called for an end to the TTIP negotiations, following a crescendo of public opposition to the talks. In October, the Walloon parliament in Belgium nearly blocked the provisional application of TTIP’s little brother, CETA, the Canada-EU trade deal. This led Wolfgang Münchau, a columnist for the Financial Times, to conclude that CETA and TTIP are as popular today in Germany as the basing of medium-range nuclear missiles in the 1980s was.

Fundamental to European disenchantment with TTIP (and to a lesser extent CETA) has been the issue of how governments and investors settle disputes. The US and EU already have huge investments in each other’s economies, so there seems little economic rationale for a new agreement on investment protection. But the two sides wanted to use TTIP to supersede existing investment treaties between member-states and the US, and pioneer an arbitration mechanism that could serve as a gold standard for other countries with less advanced judicial regimes to follow. Critics worry, however, that such a system could offer US corporations a more promising, and less democratically accountable, route to litigate against European governments. They fear this could end up restricting EU policies and could force European societies to accept, for instance, the privatisation of healthcare systems, the use of genetically modified crops or the use of hydraulic fracking to extract oil and gas resources. European governments have been ineffective in responding to the mix of rising anti-American sentiment, scaremongering by anti-TTIP lobby groups and legitimate concerns about how protection given to investors could impact a government’s right to regulate.

EU politicians should be wary of #Trump. But #TTIP had ground to a halt well before he was elected.

When France and Germany faced growing opposition to TTIP, the UK was crucial to moving a transatlantic trade deal forward. Now, Brexit removes one of the strongest pro-trade voices from the club. Priorities have shifted, and London faces a series of tough negotiations with Brussels to minimise the damage to its existing trade ties by leaving the EU. And as it seeks to strengthen its bargaining position with the Commission, Downing Street is cosying up to Trump.

Instead of building a bridge between the US and the EU, London may leverage its ‘special relationship’ with Washington in its Brexit negotiations with Brussels. A US-UK trade accord was on the agenda of Theresa May’s meeting with Donald Trump in late January. A quick trade deal would be politically meaningful for both sides: Trump could boost his pro-trade credentials and May could show that Britain has trade options beyond the EU. Unfortunately, it could also give her a false sense of strength in the negotiations with Brussels.

Any future EU trade deal could collapse if governments fail to win public support for it. The European Court of Justice will probably follow the opinion of its advocate-general on the division of trade competences between the European Council and the Commission. This opinion, published in December, holds that all EU trade agreements that contain a substantial investment dimension – as CETA does, and TTIP would – are ‘mixed’. That means that they should be ratified by national (and regional) parliaments, not just the European Parliament. The Parliament signed off on CETA on February 15, but given CETA’s near-death experience in Wallonia and the Dutch public’s rejection of the Ukraine association agreement in April, it may yet be challenged in parliaments or a referendum.

The EU can ill afford to turn its back on free trade. But to move forward, European leaders should stop pointing fingers at Trump and draw lessons from the experience with TTIP. They need to scrutinise the way their governments communicated about TTIP; decide whether to keep investment protection in future trade deals; and manage expectations about what can be delivered in what timeframe.

TTIP is a case study in how not to promote a trade deal. Too often, EU governments looked to the Commission to sell TTIP for them, and failed to take ownership of a deal they had all signed up to and that would benefit them economically and strategically. Governments also made mistakes in their arguments. In response to criticism, they often resorted to some version of “trust us, wait till we have a deal”. With mistrust of elites and EU officials running high, such statements inevitably backfire. Instead, governments should treat big trade deals, like TTIP, as a campaign. Through traditional and social media, governments should work with publics to extoll the merits of a deal, economic and otherwise, while creating the space for a fact-based debate about the social, economic and strategic impact of free trade.

The EU should consider turning its bilateral trade deals in Asia into a regional trade pact.

With TTIP dead in the water, the EU must now pivot its trade strategy towards Asia. It is in Europe’s interest to build a coalition of economies that support liberal rules-based trade and to reach strategic, standard-setting agreements with them. In a speech at the Davos World Economic Forum, Chinese President Xi Jinping denounced Trump’s protectionism. Some now suggest that Beijing and Brussels could become the flag-bearers promoting international free trade. But beyond the rhetoric, there is reason to be sceptical. Since 2013, the EU and China have been negotiating a bilateral investment treaty, but little has been achieved. There were initially high hopes that China and the EU could work together on the ‘Juncker investment plan’, but in Brussels that enthusiasm has cooled. And with no other country does the EU have as many trade disputes as with China. Instead, while continuing bilateral talks with Beijing, Brussels should vigorously pursue trade deals with China’s largest Asian trading partners, stepping into the vacuum that the US is leaving behind. The EU has already concluded deals with South Korea, Singapore and Vietnam, and talks are nearing a conclusion with Japan. There are negotiations with India and most south-east Asian states, though progress is slow. Talks have also been announced with Australia and New Zealand. The EU should now consider whether it can turn these bilateral efforts into a regional trade pact.

Finally, the EU should not give up on a transatlantic trade consensus entirely. Trade negotiations rarely die, as opposed to going into hibernation. However unlikely it seems today, Trump’s views on trade may evolve as economic conditions change. His tough protectionist line could backfire. After having tried his hand at strong-arming Beijing, Trump may find that there is a more elegant, and possibly more effective, way to bring China to play by global trading rules. And that is by nudging it in the right direction through a set of common trade norms, rules and standards, agreed with the EU, Britain and other important trading blocs. One can always hope.

Rem Korteweg is a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment