Don't imitate – innovate! Why Europe doesn't need a rival to Visa and Mastercard

The European authorities want a home-grown challenger to Visa and Mastercard. They should instead encourage European banks to support more diverse payment options.

Europeans are becoming more reliant on two US giants – Visa and Mastercard – to make payments. The European Commission and the European Central Bank (ECB) are frustrated at this situation. They see American dominance as a threat to the EU’s ability to regulate payments in a way that reflects European choices. For example, the EU was impotent when Visa and Mastercard refused to process donations to Wikileaks in 2011, following US political pressure. Nor does the dominance of US payment giants in Europe help the international standing of the euro.

To achieve ‘payments sovereignty’, the Commission and the ECB are pressuring European banks to create a new European card network, to compete with Visa and Mastercard. This reflects the EU’s all-too-common approach to strategic autonomy, which aims to replicate foreign successes rather than to innovate. The payments plan is similar to other plans to onshore semiconductor manufacturing and to create a cloud computing solution that would compete with US giants. But ‘European champions’ cannot be viable competing against businesses that enjoy global economies of scale, unless the European solution is innovative. The problem is most apparent in fast-moving technology sectors: by the time European stakeholders get behind a ‘champion’, the market will have moved on. The Commission’s hopes for a European card network illustrate these problems.

To achieve ‘payments sovereignty’, the Commission and the ECB are pressuring European banks to create a new European card network, to compete with Visa and Mastercard.

The use of cash for payment transactions in Europe is decreasing, and electronic retail payments are increasingly being made through payment card networks (see Chart 1). Some of these transactions are made through the EU’s own payment card networks – such as Girocard in Germany or Cartes Bancaires in France. Those networks usually work only within that member-state. This means that a Girocard cannot use the Cartes Bancaires network to make a purchase from a French merchant. To make sure the card still works in this scenario, national networks’ payment cards are usually ‘co-badged’ with an international network. This means the payment card will rely on an international network – usually Visa or Mastercard – for purchases with a merchant in another country.

Many European card networks were abandoned in the last decade: Luxembourg’s bancomat in 2011; the Netherlands’ PIN in 2012; Finland’s pankkikortti in 2013; and Ireland’s Laser in 2014. Payers in these countries now typically rely on Visa or Mastercard. Many new ‘digital-only banks’ (those without physical branches) do not use European networks on their cards even in countries where they are available. US influence over European payments has been growing in other ways too. In 2016, Visa Europe – which was previously owned by a consortium of European banks – was sold to Visa Inc., a US corporation. US technology firms like Apple and Google have also embedded themselves in the European payments sector in recent years, and American services such as PayPal have made inroads in online commerce. Meanwhile, European networks are falling behind in innovation.

The ECB has therefore promised to foster pan-European challengers to Visa and Mastercard – if they have “European identity and governance”. The Commission has launched a Retail Payments Strategy, calling specifically for “competitive home-grown and pan-European payment solutions … supporting Europe’s economic and financial sovereignty”. In response, 31 European banks have launched the European Payments Initiative (EPI), which intends to launch services in 2022.

A political desire for sovereignty will not in itself make a ‘European champion’ like the EPI successful in the long term. Unless the EPI has a viable business model, European businesses and consumers who pay (directly or indirectly) for the service will end up subsidising a solution inferior to today’s payment systems. Crucially, the EPI could even crowd out more innovative and beneficial alternatives.

A political desire for sovereignty will not in itself make a ‘European champion’ like the EPI successful in the long term.

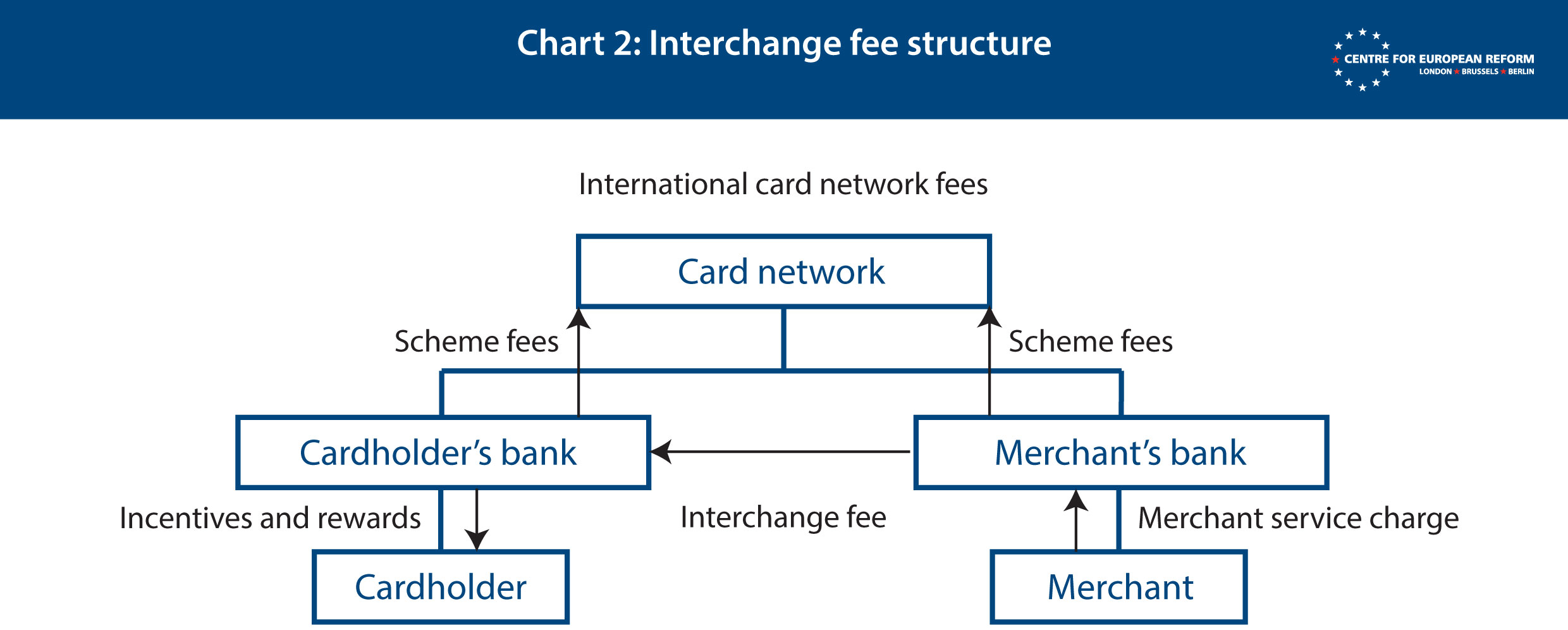

The EPI is unlikely to be viable if it uses the traditional international card network business model. Since Mastercard acquired the most successful pan-European card payment business, Eurocard, in 2002, a number of EU-wide card initiatives have failed – the Euro Alliance of Payment Schemes, PayFair, EUFISERV and the Monnet Project. The EPI would face the same problem experienced by its predecessors, of making European cardholders and merchants want to use it, while providing sufficient profitability for banks so that they will want to fund it. Established international card networks rely on ‘interchange fees’: fees paid by the merchant’s bank to the cardholder’s bank for each transaction (see Chart 2).

Through interchange fees, cardholders’ banks earn revenue from each card transaction, and therefore encourage their customers to use payment cards as much as possible (for example, cardholders’ banks may give cardholders rewards and incentives for using cards). The merchant’s bank recovers these fees from the merchant through a ‘merchant service charge’. If customers want to use their cards, merchants come under pressure to accept the cards (and pay the merchant service charge) or lose sales.

Using such a system of fees and incentives to stoke cardholder demand might have been logical for the EPI. However, the service cannot use interchange to aggressively attract cardholders, because interchange fees have been capped by EU regulations since 2015. That will prevent the EPI from growing in the way that earlier card networks did.

Visa and Mastercard have an additional related advantage over the EPI: they can increase interchange for payments between EU and foreign banks. For example, after Brexit, interchange fees on EU-UK transactions were no longer capped, and Visa and Mastercard increased them significantly, to make up for lower fees on intra-EU transactions. The EPI will probably operate only within the EU, so it will lack that flexibility.

As Chart 2 shows, both the cardholder’s and merchant’s banks also pay ‘scheme fees’ to the payment networks, which cover the costs of the network. The EPI could charge lower scheme fees than Visa and Mastercard, to help make the new network more profitable for banks. To keep costs low, the EPI could rely on a new instant payment system – which banks will probably be forced to use by the Commission – rather than building its own system. However, the EPI will still have significant costs: it will need to supplement the instant payment system, since it is not designed for card payments; it will need to develop technologies for smartphones and e-commerce payments; and it will want to replicate Visa and Mastercard’s vast additional services (such as services to identify fraud and resolve cardholder disputes). Visa and Mastercard’s scheme fees, despite large increases in recent years, are still only about 20 per cent of the total merchant service charge. It is difficult to foresee the EPI’s scheme fees being significantly lower, unless functionality and innovation suffer.

The EPI’s problems are not only financial. Once participating banks start to go into the nitty-gritty of designing the EPI, the interests of those banks will start to diverge. National networks (and their participating banks) will want their own specifications to be adopted at a European level, to minimise their costs of moving onto the new network. Countries with relatively successful national networks – such as Germany and the Netherlands – may resent their networks being replaced by (or forced to compete with) a network which would probably be more expensive and which they would have less control over. Visa and Mastercard may also try to increase their market share in some countries, by ensuring co-badged cardholders can pay by Visa or Mastercard if they wish. Today – contrary to EU law – some national networks maintain market share because local transactions using co-badged cards often use the national network, instead of Visa and Mastercard, without the cardholder being offered a choice of which network they prefer.

Given these challenges, the EPI will probably not become a sustainable and competitive enterprise if it tries to replicate Visa and Mastercard.

There is another important problem with the Commission and ECB’s plans. They undermine an objective of the EU’s 2015 ‘open banking’ reforms. Those reforms tried to encourage new payment methods, such as ‘payment initiation services’. These services give consumers an easy way to pay online using bank transfers, instead of typing in a card number. For payments in a store, a smartphone app could work in a similar way: use a bank transfer to pay, and avoid using the infrastructure (and fees) of card networks. More than 200 businesses are now authorised to provide these services in Europe (not including banks which are developing their own equivalent services), the most prominent being Klarna. If policy-makers and regulators pressure banks and merchants to support the EPI, these new payment services could struggle, and investors could be less willing to support their growth.

These forms of innovative direct payments, if successful, could be a better addition to the market in Europe than another card network. They have different benefits and shortcomings to card payments – for example, while they provide fewer rights for a consumer to dispute a payment, they can often be cheaper and safer, and they can allow merchants to get paid quicker. They could therefore have a role alongside card payments. This could achieve European policy-makers’ objective of having a pan-European means of payment, while introducing more diversity and choice.

Innovative direct payments, if successful, could be a better addition to the market in Europe than another card network.

Banks and the US networks seem to view these products as a genuine threat. Banks challenged their legality, until EU payments laws explicitly made them legal. And Visa attempted to acquire a growing platform that provides these services, Plaid, in 2020. The Plaid deal was abandoned after the US Department of Justice sought to prohibit it, in a rare case of a competition authority challenging an alleged ‘killer acquisition’. Plaid’s valuation has since vastly increased.

Open banking is, however, not yet a success. Some payment initiation services – like Trustly, Swift, Sofort and iDEAL – have gained market share in some EU member-states. But these services cannot succeed across Europe without overcoming technical, behavioural and commercial challenges. Policy-makers should focus on three areas of reform to minimise those problems.

- First, policy-makers could encourage the open banking sector to consolidate around a smaller number of products. Consolidation is necessary because merchants do not want to support hundreds of different payment services, and consumers will find a vast array of services confusing. Consolidation will help services build scale and demand. The EPI’s best chance of success might therefore be to fully embrace open banking, and act as a catalyst for some of this consolidation, rather than replicating the international card model.

- Second, regulators need to focus on ensuring open banking has appropriate governance, with input from different types of stakeholders including merchants. The EU should therefore establish an oversight body responsible for managing and implementing open banking, ensuring it works across Europe, and handling disputes.

- Third, open banking might achieve more if its success was in the banks’ interests. Banks often receive no fees for open banking transactions; worse, they forego fees they would have earned if the transactions used Visa or Mastercard. Many banks therefore do only the minimum necessary to support open banking. This limits innovation. The Commission should consider ways to address this, for example whether there is merit in allowing banks to charge fees to payment initiation service providers. One open banking provider claims savings for merchants of 90 per cent and the US Department of Justice claimed savings of 95 per cent were achievable in the US. This suggests that there is scope to give banks a larger stake in the success of open banking, while keeping the system substantially cheaper for merchants than card payments.

These changes are more technical and less exciting than replicating Visa and Mastercard’s business model with a European champion. However, they promise more innovation for consumers and merchants in the long term. The EU should therefore focus less on replicating global behemoths and more on fostering the conditions for disruptive innovation. If open banking is made fit-for-purpose, Europe could enjoy greater payments sovereignty – and also greater choice.

Zach Meyers is a research fellow at the Centre for European Reform.