Choosing Merkel's successor: None of the above?

The competition for ‘Merkel voters’ has started, and the CDU needs a leader able to keep her broad coalition of supporters together. That may well be health minister Jens Spahn.

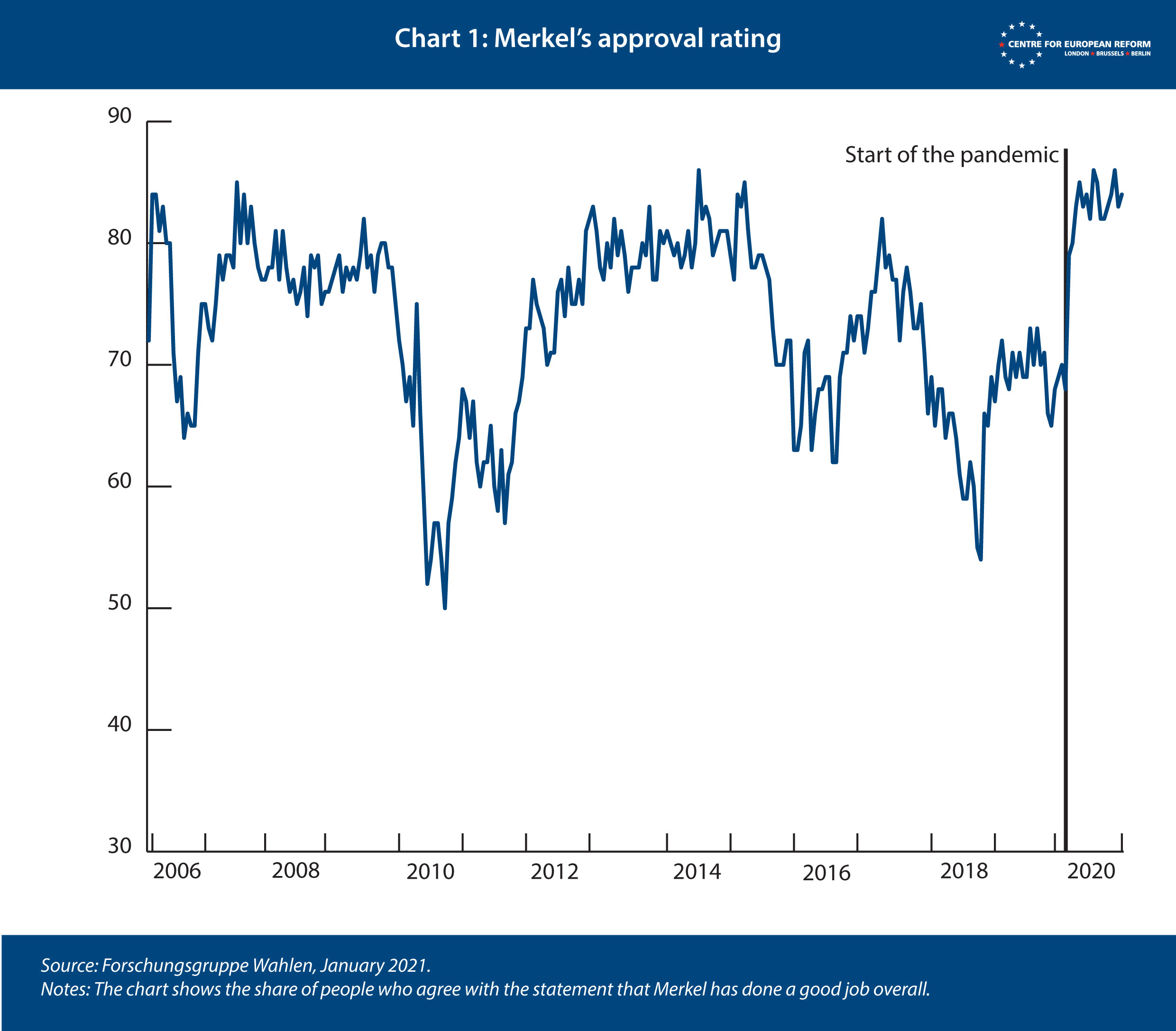

The German Christian Democrats (CDU) need a new party leader, after Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, or AKK for short, failed to fill Angela Merkel’s shoes and resigned in February 2020. This next CDU leader has a good chance of becoming the conservative candidate for chancellor in the German elections this autumn. But winning the election is another matter. Merkel’s approval rating still stands at a whopping 84 per cent after almost 16 years in power – in part because the pandemic has reaffirmed her image as Europe’s foremost crisis manager. No successor will have Merkel’s broad appeal and be able to hold onto that support once the pandemic is over. But some have a better chance than others. Considering the CDU candidates on offer, the timing in September 2021 and the opposition, the German election is wide open.

On January 15th and 16th, roughly 1,000 CDU delegates – representing the party’s local groups – will vote for the new leader. On the ballot are three men, with a run-off among the top two if the first round does not yield a majority.

- Armin Laschet, the current prime minister of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany’s most populous state. He is a generic Western German centrist conservative with some odd views on foreign policy, having expressed sympathy for Russia, Turkey and Syrian dictator Bashir al-Assad. Governing a state containing many regions at the losing end of globalisation has moderated his conservative economic instincts a little. Protecting German industry is one of his key ambitions. His management of the pandemic – public health is a state competence – is considered poor. In polls among voters in general, he stands at just 18 per cent, and at 25 per cent among CDU voters.

- Norbert Röttgen, a former federal environment minister, is also from North Rhine-Westphalia. There he lost a state election as the CDU’s candidate in 2012, and was then ruthlessly kicked out of the cabinet by his boss, Angela Merkel. He is seen as relatively progressive, despite voting against gay marriage, and a moderniser in the CDU. In recent years, he has successfully reinvented himself as the CDU’s main foreign policy expert, and is the chair of the Bundestag’s foreign affairs committee. He is smart, likable and a good speaker. After starting as an outsider in this race, he is now ahead of Laschet with 22 per cent among all voters, and on par with him among CDU voters, at 25 per cent.

- Friedrich Merz is a former CDU opposition leader in parliament and was Merkel’s arch-rival in the early 2000s. He semi-retired from politics when Merkel kept winning elections, and worked as a corporate lawyer instead. He narrowly lost the CDU leadership race to AKK in 2018. His policy views have not changed in over 20 years, and his knowledge of some key dossiers, be it Europe or digitalisation, is noticeably poor. But he compensates for that with brimming self-confidence, and his reputation as a hard-line, pro-business law-and-order conservative. Many conservative voters prefer this to Merkel’s centrism. He is the front-runner in the polls, with 27 per cent among all voters, and 29 per cent among CDU voters, and is likely to make the run-off, backed by the right wing of the party. He has the highest approval among voters of the conservative, pro-business free democrats (FDP) and the far-right alternative for Germany (AfD).

Laschet, Merz and Röttgen want to become CDU party leader in order to run for chancellor in the federal elections in the autumn. After the party leadership race, the CDU and its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union (CSU) plan to jointly pick their candidate for chancellor in the spring. Not on the leadership ballot but very much in the running for the chancellery are:

- Jens Spahn, the current federal health minister who ran against Merz and AKK in the first successor race and lost, and has now teamed up with Laschet. He made his mark early in his career as a young, brazen conservative, but re-invented himself as a more serious politician even before the pandemic started. Germany’s relative luck early in the pandemic helped him to shine in his ministerial role. Recently, the slow pace of vaccinations has started to undermine his standing, but he remains among Germany’s most popular politicians. He combines his youth (he is just 40 years old) with conservative credentials. When included in polls on the inner-CDU race he often outperforms the other three but not...

- ...Markus Söder, the head of the CSU and current state prime minister of Bavaria. Much like Austria’s chancellor Sebastian Kurz, Söder is PR-savy and re-invents himself, without losing credibility, whenever the wind turns. He has successfully transitioned from a staunch conservative and Merkel-critic to a pro-environment Merkelite front-runner. Despite Bavaria’s poor record in the pandemic – no state has witnessed more COVID-19-related deaths in Germany – he is still viewed as a successful crisis manager. He is not running for chancellor officially yet, but he is far and away the politician Germans think most suitable to become German chancellor.

Five viable contenders make for a complicated political race by themselves. But delegates will also have to consider how Germany’s political landscape has changed during Merkel’s tenure, and how she in turn re-positioned the CDU. In choosing their next leader, CDU delegates are also casting a vote on the future of conservatism in Germany.

In choosing their next leader, CDU delegates are also casting a vote on the future of conservatism in Germany.

Tweet thisBluesky thisParties like the CDU and the social-democratic SPD (and their peers in Europe) struggle to remain the broad churches (‘Volksparteien’) that they used to be. The SPD has already shrunk from a vote share of 35 per cent in the 2005 election, when Merkel came to power, to about 16 per cent in the polls today. The CDU has so far been spared that fate – despite the rise of the AfD – because it has largely managed to hold together a broad coalition of voters. The key question for September is whether Merkel was the glue.

There is good reason to believe that she was. Merkel never engaged in ‘culture war’ politics, refusing to use conflicts about values and beliefs to whip up support among party loyalists and to split electorates. Instead, she patiently waited for opportunities to settle divisive issues once the consensus in Germany was favourable. That allowed her to keep hold of centrist voters without alienating too many in the conservative wings of her party. A classic example was the decision to abandon nuclear power – a highly divisive issue in Germany – after earthquakes and a tsunami destroyed a nuclear plant in Fukushima, Japan, in 2011, even though the probability of an earthquake and tsunami on the German North Sea coast is zero. Introducing a minimum wage when public opinion clearly favoured it or allowing gay marriage to pass while voting against it are other examples. The added benefit of her approach was to soothe potential opposition voters, as they saw the government addressing at least some of their concerns.

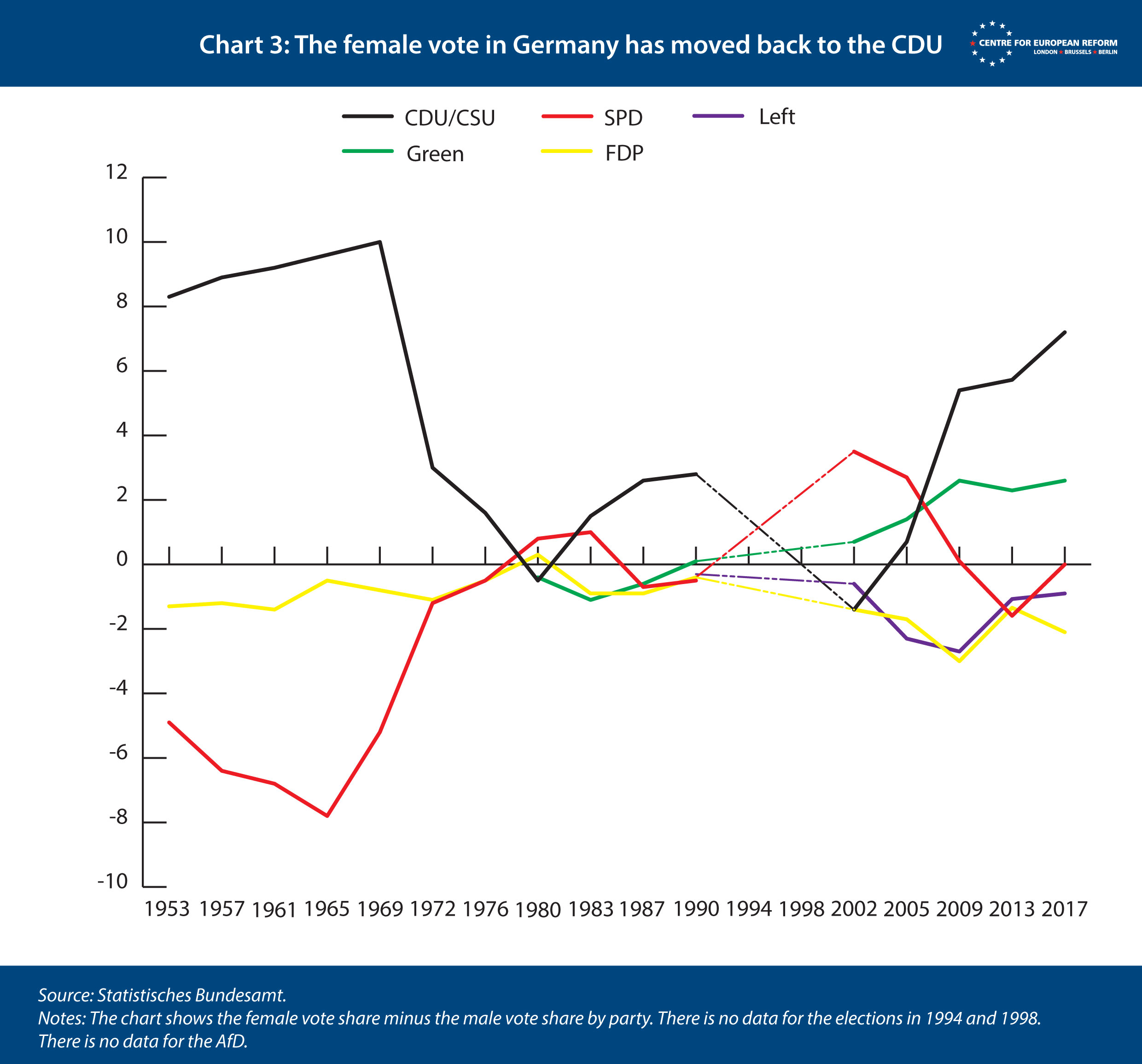

Merkel managed to win other new voters for the CDU. Consider the female vote. In the post-war period, the CDU successfully appealed to women by emphasising Christian values and the family. Chart 3 shows that the vote share of the CDU was up to 10 percentage points higher among women than men in the 1960s. That changed with the 1968 political revolts. In the last election in 2017, Merkel has widened the difference between female and male voting back over 7 percentage points. It is unlikely that one of the (male) CDU contestants above will hold on to all those voters.

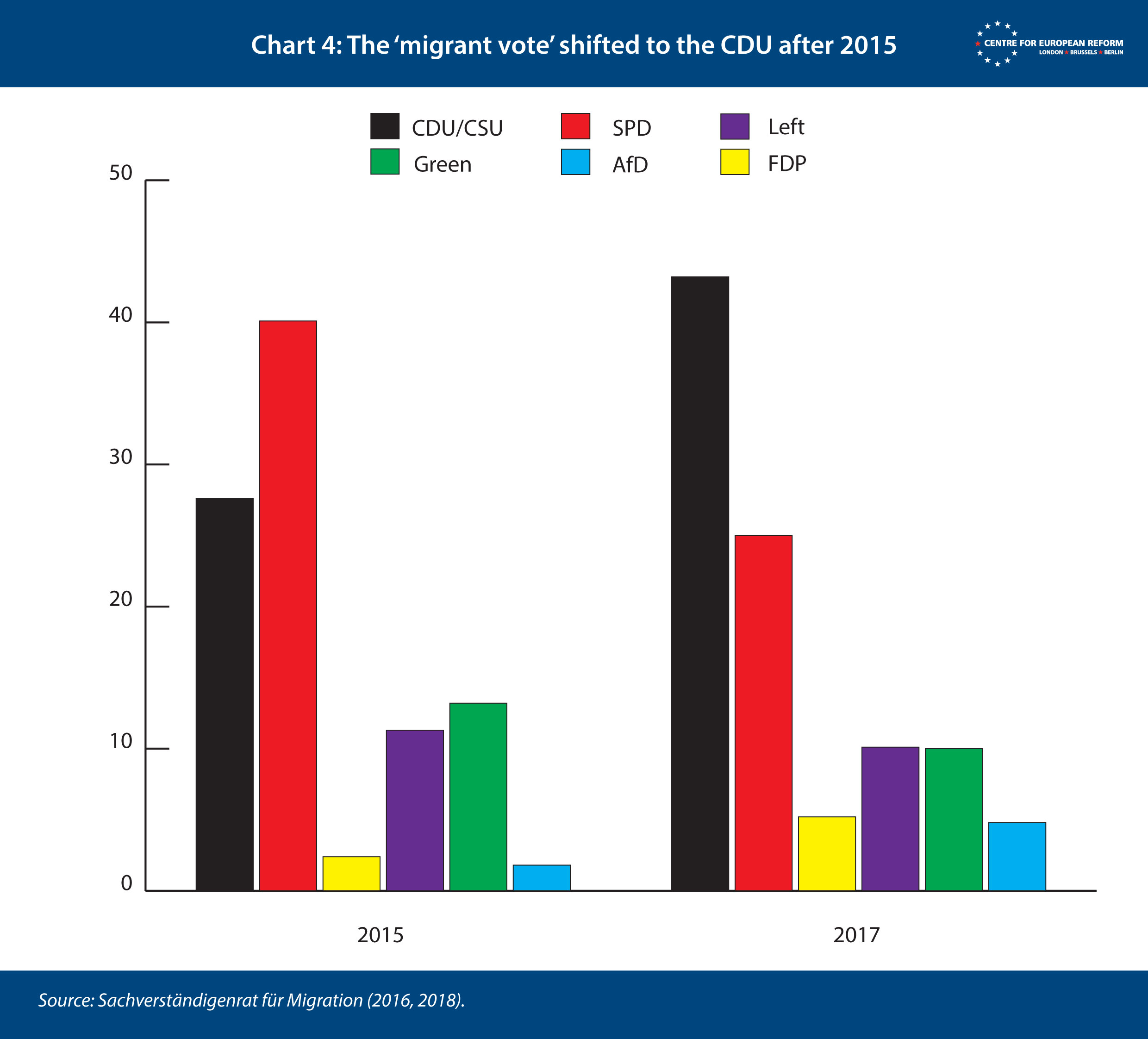

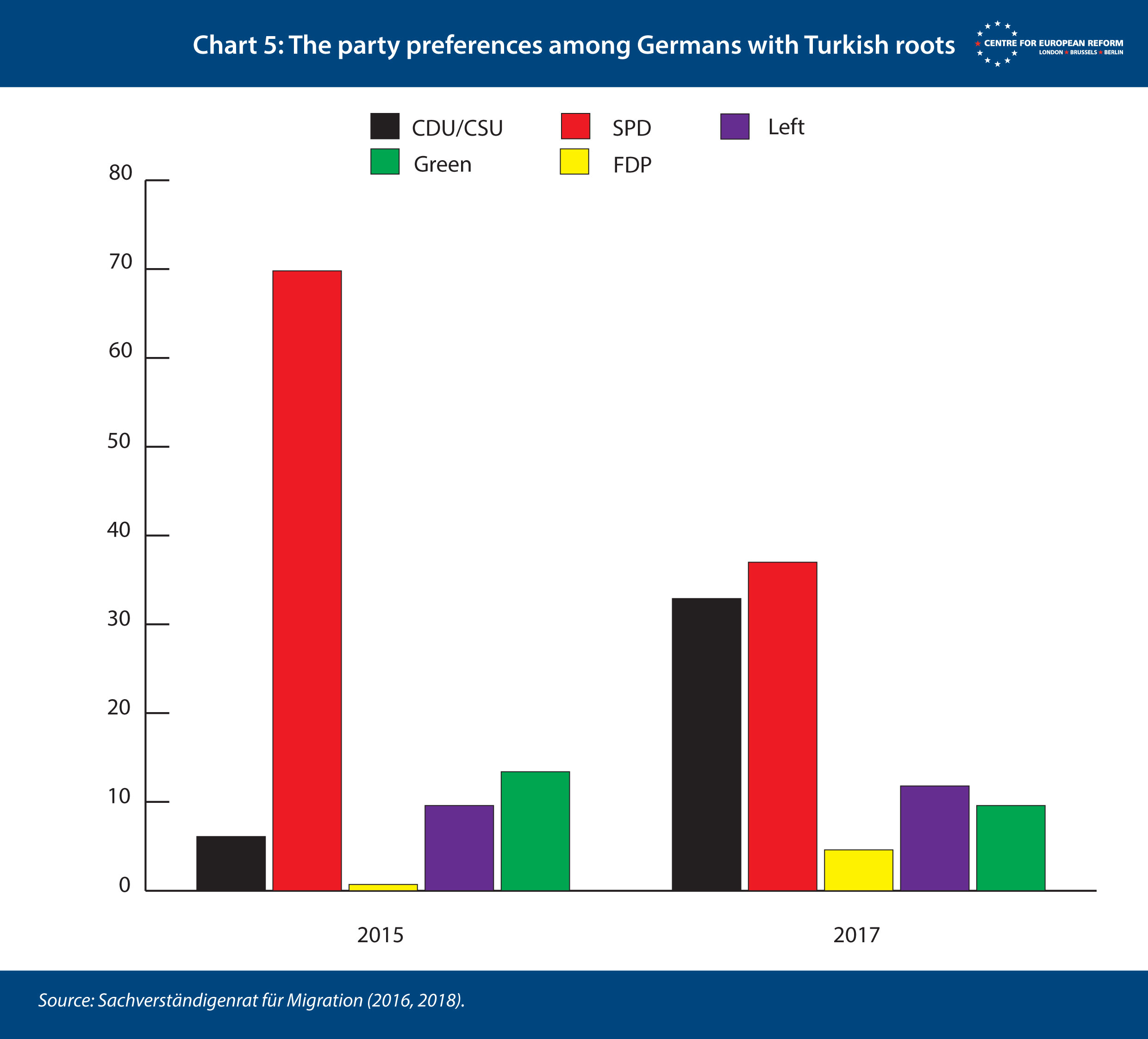

The ‘migrant vote’ has also moved towards the CDU – a key demographic, considering Germany’s high levels of immigration. Germans with at least one foreign-born parent made up roughly 10 per cent of the voting population in 2017. They traditionally favoured the SPD and other left-leaning parties for their more welcoming attitude towards migration. The CDU used to be openly hostile to immigration, and giving migrants citizenship and thus the right to vote. With the refugee crisis, the perception of the CDU changed drastically. Merkel rid the party of its anti-immigration image, and voters followed (see Chart 4): the CDU is now polling better among those with at least one foreign-born parent than among those without. The shift is most pronounced among Germans with Turkish roots (see Chart 5).

Merkel rid the CDU of its anti-immigration image. The CDU is now polling better among those with at least one foreign-born parent than among those without.

Tweet thisBluesky thisWinning those voters – centrists, women and those with foreign roots – led to spectacular results for the CDU. In 2013, Merkel came close to an absolute majority (the only time a party won an absolute majority in a federal election was the CDU in 1957 under Konrad Adenauer). Neither the FDP nor the AfD made it into the Bundestag. Only after the refugee crisis did the AfD manage to establish itself to the right of the CDU.

This leaves the CDU post-Merkel with three options:

- Röttgen’s proposed strategy is to continue with Merkel’s centrist course of modernisation. But this risks losing more voters to FDP and AfD, and his progressive views lack broad party support.

- Merz’s course is to move the CDU back to the right to try to reclaim votes from the AfD. But this risks yielding the centre to the Greens, which the CDU has now identified as its main rival.

- Laschet and Spahn will try to keep the centre and the conservative wing together. But like AKK, Laschet is prone to making gaffes, and lacks a distinctive profile. Laschet also polls poorly with the general population, so even if he becomes party leader, Spahn – who is already sounding out party members – may well become the CDU’s pick for chancellor.

Could Söder make the race for chancellor at the end? The Bavarian may fear that performing badly in a federal election could undermine his standing in his home state. But if Söder wanted to become chancellor, his best bet would be to team up with Röttgen as party leader, who has said he would consult with Söder on who was best-placed to win. If on Saturday Merz faces off against Röttgen, delegates might conclude that Röttgen and Söder are the best team for the CDU’s future.

In the federal election, the joint candidate of CDU and CSU will run against Olaf Scholz from the SPD and probably Annalena Baerbock from the Greens, both of whom are strong candidates. The former is highly experienced in both state and federal government and will present himself to voters as a safe pair of hands; while the latter is a charismatic party leader full of ideas for Germany’s future and heads a confident party keen to govern. All will be campaigning with the end of the pandemic in sight. In such a political climate of optimism and new beginnings, a party that has been in government for 16 years may struggle to attract voters in search of change, whether it is led by a fresh face or not.

After the pandemic, in a political climate of optimism and new beginnings, the German conservative party may struggle to attract voters in search of change.

Tweet thisBluesky thisWith Merkel’s departure, Germany and Europe will lose an experienced and gifted stateswoman. Her cautious political style has left some allies frustrated with an inward-looking Berlin, seemingly refusing to embrace a leadership role. But Merkel has been a status quo chancellor for a status quo people. She did not see her role as mapping out large reforms, but as reliably managing incremental progress from within the constraints set by Germany’s national interest and the need for consensus. She had a good sense of the rare instances when German voters were willing to embrace a new course. A less experienced leader will struggle to do the same.

Any future CDU chancellor will thus start from a position of managing the status quo, preserving what has been achieved, maintaining the crucial relationship with the US, and not risking Germans’ support for European integration. Europe should not expect a Macronian reform agenda for Europe from Röttgen, nor does it need to fear a Chancellor Merz (for his orthodox economic views) or Laschet (for his odd foreign policy ideas). Röttgen’s ideas will not convince a party of reform-sceptics; Merz’s tough stance on eurozone integration would be moderated by the conservative imperative of preserving economic stability in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic; and Laschet’s more outlandish foreign policy views would not survive in office for fear of alienating the US.

The CDU/CSU may well come out as the biggest party in the elections in the autumn. Unless the Greens, the SPD and the Left can and do form a centre-left coalition, the Conservative candidate will become German chancellor. But as important as the chancellor will be the CDU’s coalition partner. Under Merkel, the coalition partner has hardly mattered for Europe. It was she who decided the course of Germany’s policy. With Olaf Scholz in the finance ministry, the SPD made some progress in shaping European policies such as the recovery fund, but Merkel’s role remained pivotal. A new CDU chancellor would not have the same standing, opening a space for meaningful political debates on Europe. A different coalition under fresh leadership may not have Merkel’s experience or authority. But it could well mean that Germany contributes more ideas to the European debate.

Sophia Besch is a senior research fellow and Christian Odendahl is chief economist at the Centre for European Reform.

Add new comment