Brexit and services: How deep can the UK-EU relationship go?

- In the Brexit debate, trade in services has played second fiddle to trade in goods and manufacturing supply chains. Yet, if the UK is to leave the single market, British services exporters will face substantial new constraints on their ability to export to the EU.

- While the EU’s single market for services is incomplete, it has liberalised services trade to a far greater extent than any comparable free-trade or regional agreement. In some sectors, trade in services between member-states is freer than between the federal states of the US.

- Outside the single market, international services firms selling into a foreign market largely do so from offices based in the country they are ‘exporting’ to. But UK services trade with the rest of the EU, at least in some sectors, is far more reliant on cross-border supply from the UK’s territory into the other 27. Whereas 67 per cent of UK financial services (excluding insurance) supplied to the EU are exported cross-border, the same is true for only 28 per cent of those sold to the rest of the world.

- There is scope for a future trade deal to be relatively ambitious in some areas, such as ease of establishment, recognition of qualifications and the temporary movement of people. But cross-border services trade – from the UK into the EU – will face new restrictions.

- Leaving the single market would lead to a change in the composition of UK services trade with the EU. Fewer services would be provided cross-border, and there would be a relative increase in the proportion being provided via the establishment of a commercial presence within the EU-27. This will inevitably lead to some well paid jobs ‘moving’ out of the UK to the EU-27, with knock-on consequences for secondary employment in the domestic UK supply chain and British tax receipts.

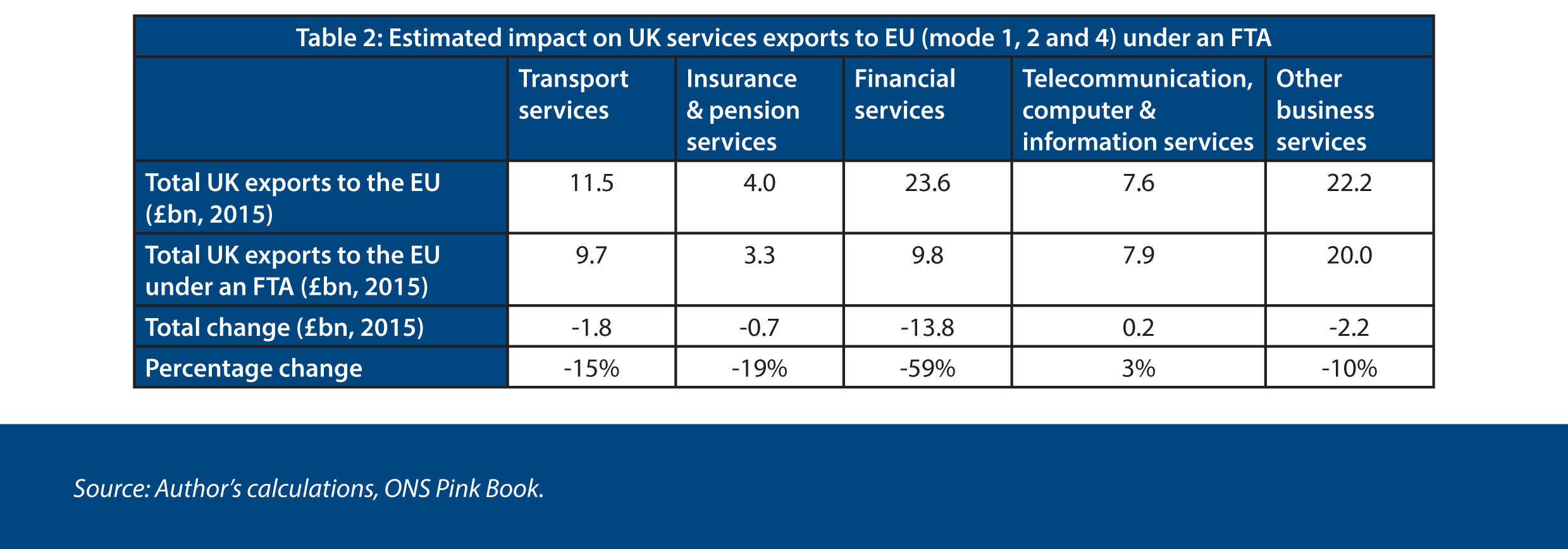

- A large shift in the composition of UK services exports would have consequences for the UK’s trade balance. If the composition of UK services supplied to the EU matched those to the rest of the world, we estimate that financial services exports to the EU (minus insurance and pensions) would be around 60 per cent lower. The export of insurance and pension services would be 19 per cent lower. Business services (including law, accountancy and professional services) exports would be ten per cent lower.

In 2017 services accounted for 45 per cent of total UK exports, or £277 billion. The EU received 40 per cent of British services exports, the highest proportion of any UK trading partner. Unlike goods, where it runs a deficit, the UK ran a total trade surplus in services of £112 billion.1

Yet, in the Brexit debate, trade in services has played second fiddle to trade in goods and manufacturing supply chains. The British government, with its desire to leave the EU’s single market, has conceded that, post-Brexit, British services exporters will not have the same access to the EU market as they do currently.2 The UK is now seeking to stretch the EU’s interpretation of how deep a trading relationship in services it is willing to have with non-EEA countries.

This policy brief examines how liberal EU-UK services trade can be if the UK indeed leaves the single market. It begins with an introduction to trade in services, followed by an overview of existing single market provisions in a few important sectors. It proceeds to compare and contrast them with equivalent provisions in the EU’s most recent, comprehensive free trade agreement (FTA) with a third country, the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement. It specifically focuses on four services sectors in which Britain has a comparative advantage: finance, insurance, legal and accountancy. It then examines the constraints placed upon the EU when it comes to its ability to go further on services liberalisation than in the past, and explores the extent to which the UK could stretch existing provisions. The policy brief concludes with an economic assessment of the impact of leaving the single market for Britain’s services firms, specifically focusing on the extent to which firms will have to move operations into the EU.

While Brexiters have a tendency to say the single market in services does not exist, leaving will inevitably lead to reduced access to the European market for UK-based services suppliers. What that looks like in practice has not received the attention it deserves. At best, an EU-UK free trade agreement could see ambitious provisions on the recognition of qualifications, investment, and the temporary movement of people. However, this policy brief argues that any arrangement that sees the UK leave the single market will inevitably lead to new barriers to services exports from the UK to the EU. The impact of these barriers will vary by sector, with highly regulated industries, such as financial services, being more affected.

We estimate that, were the EU and UK to trade services under the provisions of a free trade agreement (which, in practice, offer little more than the access afforded under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules), rather than as a member of the single market:

- UK exports to the EU of financial services (minus insurance and pensions) would be 59 per cent lower;

- UK exports of insurance and pension services would be 19 per cent lower; and

- exports of other business services (including law, accountancy and professional services) would be ten per cent lower.

The magnitude is of greater importance than the exact percentage change, but it is notable that they paint a similar picture to other independent studies.

Any new post-Brexit barriers to UK services exports to the EU will have second-order negative consequences for jobs, investment and the tax take in the UK. While these consequences are unfortunate, if the UK is to extricate itself from the single market, they should be viewed as an inevitable consequence of British political decisions.

Trade in services

When politicians and the media talk about trade they nearly always focus on goods. This might be because services trade is often intangible and complex. Unlike goods, an individual service can be traded or supplied in multiple ways.

Take medical services, for example. An American patient living in the US could have a plastic surgery consultation with a British private hospital over Skype. Alternatively, the patient could fly to the UK to have a personal consultation. If the patient did not want to travel, and felt Skype was too impersonal, they might decide to go to one of the private hospital’s Houston-based clinics. If the patient were a prized client, the hospital might fly over one of their best British surgeons for a short period of time to consult with the American patient in person.

In all four examples, the same service – a medical consultation – has been provided, but it has been supplied in four different ways. These are known as mode one, two, three and four respectively.3 Box 1 outlines what is covered by each mode.

While the four modes are conceptually distinct, in practice the liberalisation of one mode of supply often has implications for another.

While the WTO has gone some way towards lowering barriers to trade in services, it has only been able to do so much.

Tweet thisBluesky thisFor example, while most services are ‘traded’ through commercial presence (mode 3), businesses which establish themselves abroad may also be reliant on modes 1 and 4; it is easier to establish a branch of a bank in another country if you are also able to parachute in staff to get it off the ground (mode 4), and continue to carry out certain processes cross-border from the home office while the subsidiary is finding its feet (mode 1).

The preference for trading via a commercial presence makes sense when you consider that liberalising mode 1 and 4 remains difficult. Barriers come in many forms and include countries actively discriminating against foreign suppliers; arduous qualification requirements placed on temporary workers; non-transparent, complicated and discriminatory licensing regimes; a refusal to recognise foreign-derived qualifications as equivalent; and constraints on where a supplier can be physically located.

While the WTO has gone some way towards lowering barriers to trade in services, it has only been able to do so much. All parties to the WTO’s General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) have general obligations and specific commitments. General obligations automatically bind all parties to the agreement while specific commitments vary by member.

For example, GATS members make sector-specific commitments which constrain their ability to restrict or limit market access (for example, limitations on the number of foreign services suppliers, or total number of services transactions) and discriminate in favour of domestic suppliers (confusingly known as ‘national treatment’ – which means that the government has to treat a foreign company as if it were a domestic one). They are then subject to a general obligation to provide the same access afforded to the services providers of one member to those established in another (known as ‘most favoured nation’).4 However, coverage, particularly when it comes to modes 1 and 4, is patchy, and reservations abound. (There are few reservations with regard to mode 2 because not many governments want to prevent people visiting their country from using its services.)

It is significantly more difficult to open services markets than good markets to trade.

Tweet thisBluesky thisFurthermore, WTO members have the right to retain measures relating to qualification and licensing requirements and technical standards, so long as they are not an unnecessary barrier to trade (and the precise definition of ‘unnecessary’ remains largely undefined). In the case of financial services, a prudential carve-out also exists, ensuring that no member is prevented from taking measures to ensure the integrity and stability of the financial system.5

Conversely, while the EU’s approach to internal services liberalisation is much maligned, it has managed to go much further than the WTO. Although barriers to trade in services between member-states exist across most sectors, and the single market for services is not as developed as the single market for goods, it remains the most comprehensive example of multi-country services liberalisation in the world. Indeed, in some areas it has liberalised services trade between its members further than some countries have managed within their own borders. For example, the EU has been much more successful in developing a framework for the mutual recognition of professional qualifications than the US.6

It is significantly more difficult to open services markets than goods markets to trade. Many of the barriers to services trade are regulatory in nature; unlike goods, the quality and safety of services are difficult to assess at the border. This makes risk harder to manage. If you are not sure whether the medical training offered in another country is equivalent to that required in the UK, it is safer to ask a foreign doctor to retrain before practising in Britain, rather than risk them killing someone. Similar logic applies to lawyers and other regulated professions. In the case of financial and insurance services, the risk to consumers – and the domestic financial system – attached to imports of many services is often too much for regulators and politicians, still reeling from the aftershocks of the financial crisis, to contemplate.

It is notable that even with the EU’s efforts to replicate domestic regulatory and political institutions at the supranational level, services liberalisation has only been able to go so far, and barriers remain. This, and the fact that no other group of countries has gone further, suggests that there are entrenched political limits to what can be achieved when it comes to services liberalisation, in the absence of full political and economic integration. If, as appears to be the case, the UK intends to free itself from the EU’s collective rule book, shared institutions and supranational enforcement regime, new barriers to trade in services will inevitably arise.

Single market versus FTA

The EU’s recent FTA with Japan gives a good indication of how much openness in services the EU is willing to tolerate without the rules and institutions of the single market.7 The following section takes EU-Japan as a baseline for an EU FTA with a developed country, and explores the subsequent implications for the UK.

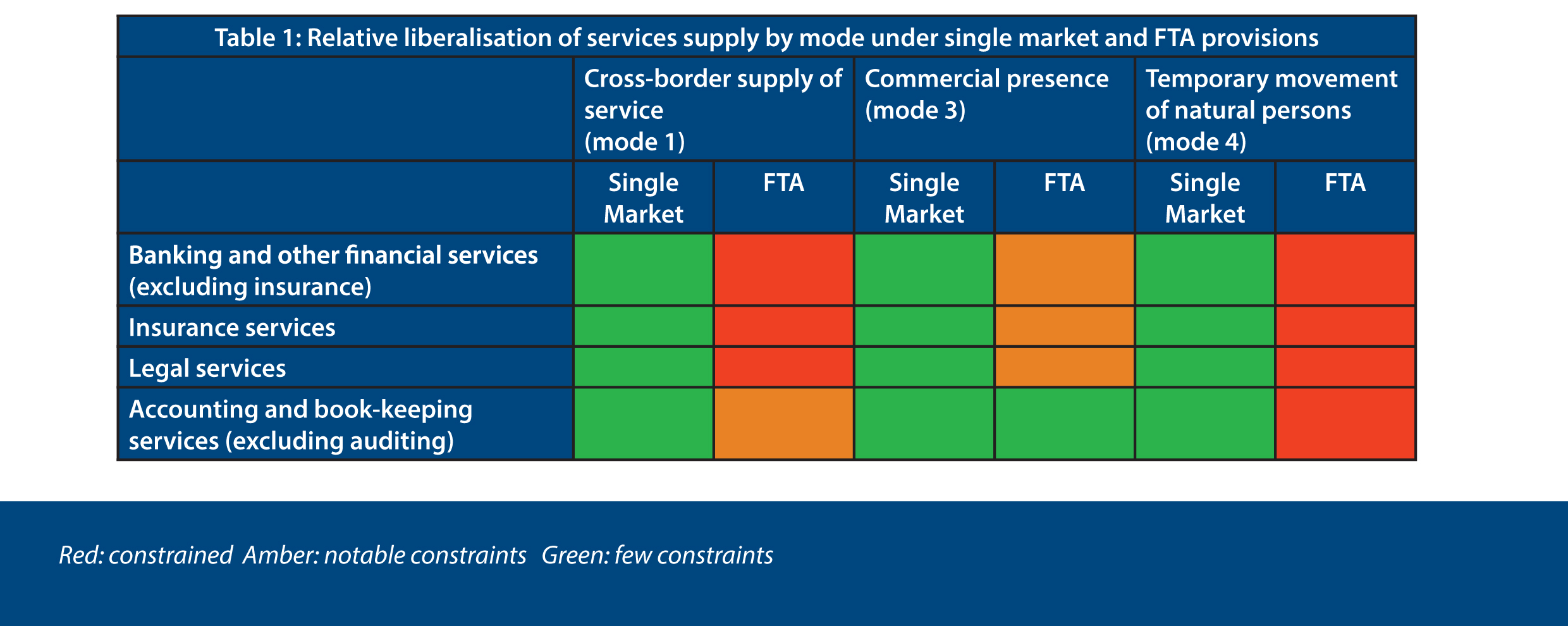

Table 1 contrasts the provisions for four sectors under the terms of the EU-Japan agreement with those afforded within the EU’s single market. These sectors are: banking and financial services (excluding insurance); insurance services; legal services; and accountancy and book-keeping services (excluding auditing). These sectors were chosen for their relevance to the UK economy, and to provide a snapshot of the issues that would potentially face UK firms exporting into the EU post-Brexit if the EU and UK were to enter into an FTA.

It is worth noting that the FTA commitments outlined below go little further than the commitments made by both parties in their WTO GATS schedules. Note also that mode 2 services provision – consumption abroad – would remain broadly liberalised under an FTA scenario, so it is left out of the discussion.

Cross-border supply of services (mode 1)

EU FTA provisions, including EU-Japan, offer little more than standard GATS provisions in cross-border services trade, and significantly less than single market membership. This is particularly an issue for more heavily regulated sectors such as financial and legal services. For example, while a bank licensed to operate in a state that is part of the EU’s internal market is immediately able to sell to customers across the EU/European Economic Area (EEA), under FTA provisions there are significant market access restrictions, and reservations relating to national treatment. And as with GATS, an FTA does not do much to address regulatory issues around authorisations and licensing, with the processes varying between member-states. In practice, this pushes companies towards establishing subsidiaries within the EU, which are quite expensive – so some will choose not to.

Under EU FTA provisions, financial market access commitments only exist for data processing software, advice and other things that support financial services (but not for banks’ main job – lending). Additionally, only firms with their registered office in the EU can accept deposits of investment funds’ assets. Hungary lodges additional reservations in the EU’s FTAs, allowing non-EEA companies to provide financial services in Hungary solely through the creation of a branch or subsidiary.

As regards insurance, under FTA provisions all EU member-states reserve the right to restrict cross-border market access, committing to liberalise their markets only for a few specific types of direct insurance largely related to the transportation of goods. Specific reservations vary member-state by member-state. Finland, for example, requires insurance brokers to have a permanent place of business in the EU.

When it comes to the cross-border provision of legal services, again, there is a big disparity between the obligations placed upon single market members, and those contained within an FTA. Generally speaking, within the EU, a lawyer qualified in, and operating out of, the UK can sell and provide legal services cross-border to a client in any other member-state (although in practice country-specific expertise remains highly valued by clients).8 In contrast, an FTA with the EU will contain many reservations, particularly with regard to market access. Most EU member-states make commercial presence or establishment a condition of market access. Some, including Belgium and Cyprus, place nationality-based conditions (Swiss or EEA) on representation in domestic courts and membership of the domestic bar.

For financial services, UK providers could supplement the limited access provided by an FTA by making use of the EU’s equivalence regime.

Tweet thisBluesky thisLess regulated sectors, such as accounting and book-keeping services, would face fewer restrictions under an FTA-type relationship, but still more than if the UK remained in the single market. Under an FTA, the cross-border supply of accountancy and book-keeping services from the UK would remain mostly liberalised, at least at the pan-EU level, where there are no reservations. But member-states have their own restrictions. In Italy, for example, non-EEA accountants and book-keepers have to be based in Italy to provide services. Hungary maintains the right to place any restrictions on cross-border supply it sees fit.

For financial services, UK providers could supplement the limited access provided by an FTA by making use of the EU’s equivalence regime. This is a process by which the EU unilaterally allows some financial services to be provided cross-border from another country, provided it deems the regulatory regime to be of an equivalent standard to its own. For example, an EU investment firm will be able to delegate portfolio management to a UK firm so long as a co-operation agreement is in place between the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the competent authority in the host state. However, the EU will only grant equivalence for a small number of products, and even for some products where equivalence is technically possible, such as mergers and acquisitions advisory services, there are no prior examples of it being authorised.

On the regulatory side, there are precedents (including in the EU-Japan agreement) for the EU establishing joint regulatory forums within its FTAs. In essence, these focus on sharing information and consulting on new rules, resolving disagreements and ensuring that domestic regulations or standards do not discriminate against the non-EU providers unnecessarily. Both parties also commit to work together in international regulatory forums.9

If the UK exits the single market, the limitations outlined above point to UK-based suppliers facing a significant reduction in cross-border access to the EU services market even if an FTA is agreed.

Commercial presence (mode 3)

While it is easier for a British person or company to establish themselves in another EU-27 country within the single market than under the provisions afforded by an FTA, at least with regards to companies, EU FTA provisions are still fairly liberal.

For financial services, the big difference between single market and FTA mode 3 access relates to setting up branches, which are cheaper to establish than subsidiaries because they do not need to be fully capitalised. Within the single market, any financial services firm established in the UK can establish branches in any other EU/EEA member-state with relatively few additional requirements. Branches can service clients from across the EU/EEA. While, generally speaking, under the provisions of an FTA foreign firms fully established within the Union can trade across the EU on the same conditions as local firms, European branches of non-EU companies are not allowed to trade across the EU under host-state rules. Furthermore, the ability of a UK bank to set up branches across the EU would vary between member-states, and also by industry. For example, in the case of Portugal and pension fund management, direct branching from non-EU countries is not permitted. In Italy, a non-EU company cannot manage securities settlement as a branch, and must incorporate.

Conditions are much the same for insurance services. FTA provisions ensure establishing a subsidiary is fairly straightforward, although there are some additional conditions attached in some member-states, but setting up branches can be more difficult. In Portugal, Spain and Bulgaria, for example, direct branching is not permitted for insurance intermediation (brokers who connect consumers with relevant providers).

Within the single market, a lawyer is able to open an office in any other member-state.10 Under an FTA, companies or firms may sell across the single market once established in an EU member-state. However, additional conditions attached to establishment vary by member-state. For example, 90 per cent of the shares of a Danish law firm must be owned by lawyers with a Danish licence, lawyers qualified in a member-state of the European Union and registered in Denmark, or law firms registered in Denmark. It is usually necessary for a practising lawyer to hold local qualifications. All member-states have non-discriminatory bureaucratic hurdles that may apply to any lawyer seeking to practise in its territory.

As with mode 1, for accounting and book-keeping services (excluding auditing) there are few restrictions on establishment under FTA provisions, relative to the single market, but some do exist. In Austria, for example, the capital interests and voting rights of accountants with non-EEA qualifications working in an Austrian enterprise may not exceed 25 per cent. In France, the provision of accounting and book-keeping services by a foreign service supplier is conditional on a decision by the Minister of Economics, Finance and Industry, in agreement with the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Temporary movement of natural persons (mode 4)

Under freedom of movement provisions, there are few restrictions on UK nationals temporarily delivering services contracts in other member-states, be they short-term business visitors, intra-corporate transferees, contractual services suppliers or independent professionals.

Existing EU FTAs, where the focus is exclusively on temporary provision, do not come close to achieving this level of mobility. In theory, short projects involving mode 4 may be undertaken under the EU’s FTAs, but in practice, no matter the stated obligations, providers often do not do so because the partner country’s immigration regime does not reflect the FTA.

Short-term business visitors to the EU can stay up to 90 days within any six-month period, and intra-corporate transferees can stay up to three years, with possible extension at the discretion of member-states. For contractual services suppliers and independent professionals, the rules vary depending on the sector, the employment status of the person providing the services, and the reason for their visit. Member-states retain a lot of control, with many refusing to bind themselves to big immigration commitments. And many put extra conditions on any commitments the EU makes in its FTAs.

Broadly speaking, a contractual services supplier can enter the EU to deliver a contract that does not exceed 12 months, subject to conditions. These conditions stipulate that: the person must have a university degree or equivalent qualification alongside any professional qualifications required to supply the service; an independent professional can enter the EU to deliver a contract that does not exceed 12 months; they must have at least six years’ of professional experience in the sector, a university degree and relevant professional qualifications.

The EU does not make mode 4 commitments for all sectors or sub-sectors in its FTAs. In the case of financial services and insurance, mode 4 provisions exist only for advisory and consulting services. Some countries, including Austria, Bulgaria, Romania and Slovakia make contract offers to non-EEA financial advisory firms and independent professionals subject to an economic needs test, such as being able to demonstrate they are essential to the working of an organisation. Hungary is not bound by any provisions in this area.

The same is true for contractual legal services suppliers and independent professionals where some countries make contract offers subject to an economic needs test. For accounting and book-keeping services, the EU does not make any mode 4 commitments vis-à-vis independent professionals.

Mutual recognition of qualifications

Within the EU’s single market, when a Briton moves to another member-state to work and gives formal proof of a UK qualification, regulators must assess whether it is equivalent to their own and cannot make a flat-out refusal. If regulators say there is a substantial difference, the applicant may be asked to take an aptitude test or go through an adaptation period. If the Briton is only temporarily moving to provide a professional service, the regulator might demand information about the service and the provider.

Specific rules apply for certain professions, as is the case for lawyers. Any qualified lawyer in any member-state is able to provide legal advice cross-border (mode 1) on a temporary basis in any other member-state without notifying the authorities. With regard to establishment, any UK lawyer is able to establish in any other member-state subject to registration with its competent authority. After three years of practice a UK lawyer can choose to join the host state’s professional body, but this is not mandatory.

EU FTAs are much less comprehensive. The recognition of non-EEA professional qualifications varies by member-state. The EU-Japan FTA does not provide for mutual recognition of qualifications, but instead creates a committee that will, in the future, provide recommendations as to where opportunities exist for mutual recognition and encourage competent authorities to engage in negotiations.

The UK position

In the UK government’s July 2018 white paper, it presented its aspirations for the future post-Brexit relationship with the EU.11 While much of the attention since has focused on its proposals on customs and a common rule-book for goods, the paper also outlines the UK’s services ambitions.

The UK emphasises that both parties will retain the right to regulate services as they see fit. Subsequently, it explicitly accepts that the proposed new arrangements mean that “the UK and EU will not have current levels of access to each other’s markets.”

The UK proposes an arrangement that:

- Covers all services sectors and “deep” market access commitments, and removes the vast majority of ‘national treatment’ reservations with regards to both cross-border provision and provision via establishment. In practice, this would mean that there were no restrictions on the number of British firms that could operate in the EU and that UK-based services providers would be subject to the same rules as those based in the EU, except in exceptional circumstances.

- Contains “best-in-class arrangements on domestic regulations” and the need to ensure that all new measures are “necessary and proportionate”. It is not immediately apparent what “best-in-class” means in practice.

- Includes supplementary provisions for professional and business services, using the example of legal services, where it argues that joint practice between UK and EU lawyers should be permitted. It does not cover other areas. On financial services, the UK maps out a much broader framework, which is elaborated upon later in this section.

- Goes further than existing EU trade agreements on mutual recognition of professional qualifications. The UK-EU agreement would be broad in scope and cover those operating either on a permanent or temporary basis across borders. In practice, it appears that the UK is asking for a framework much the same as that afforded by the EU’s Mutual Recognition of Qualifications Directive and single market membership.

- Re-states its aim to end free movement of people. However, it intends to build on existing GATS commitments as part of a mobility deal with the EU (and these would also be offered to the UK’s other close trading partners). It will seek a reciprocal arrangement that allows for short-term business visas. The UK also hopes to agree reciprocal commitments on intra-corporate transfers and says it wants to discuss potential measures to “facilitate temporary mobility of scientists and researchers, self-employed professionals, employees providing services as well as investors.”

As with other services, the UK accepts, in principle, that its decision to leave the single market means that UK-based financial services providers will no longer be able to make use of the EU’s passporting regime and sell into the EU cross-border on the same terms as now. However, it argues that the EU’s existing third country equivalence regime – whereby the EU unilaterally allows foreign firms to sell into the EU if it deems the financial regulatory regime of the country within which they are based to be equivalent – is not good enough.

The UK accepts the need for regulatory autonomy, both for the UK and EU, and thus the ability of either party to unilaterally restrict access, but seeks to build on existing equivalence provisions. It proposes that:

- The EU’s existing equivalence regime is expanded to provide greater coverage, to account for existing cross-border business activity.

- Both parties should reciprocally grant equivalence rulings in all areas where the EU currently operates an equivalence regime from the end of the transition period. It argues that this should be possible because the EU and UK now have “identical rules and entwined supervisory frameworks”.

- Future equivalence decisions should be based on an agreed set of common principles. Both parties would be transparent and principled about equivalence decisions, and a withdrawal of access should only follow a period of consultation and mediation.

- Equivalence should be accompanied by extensive supervisory co-operation and regulatory dialogue so as to facilitate co-operation between the EU and UK in international forums and reduce the number of barriers erected by future regulatory divergence.

How far is the EU prepared to go? (From Japan to Chequers)

The EU has not yet put forward a detailed proposal to the UK. However, in the draft political declaration setting out the framework for the future relationship between the EU and UK, both parties lay out the broad parameters of what they hope to achieve on services in a future partnership agreement, if Britain leaves the single market (as the UK says it wants to).

The political declaration is relatively vague, but sketches out a future relationship that would liberalise the right of establishment beyond that offered in previous FTAs, making it easy for UK companies to incorporate in the EU-27. The UK and EU would aim for substantial sectoral coverage, covering all modes of supply. The declaration also proposes negotiations on specific transport services agreements, to ensure “continued connectivity between the UK and EU”. On regulation, both the EU and UK hope to create a framework for voluntary regulatory co-operation and the development of appropriate arrangements when it comes to the mutual recognition of regulated professions. With regard to the movement of people, the political declaration largely focuses on the UK’s desire to end free movement of people, but previous speeches by Michel Barnier, the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator, suggest the EU will seek “ambitious provisions”.12

It is important to understand that the EU-UK trade negotiations will not happen in a vacuum. The EU has made commitments to other countries, as part of many different agreements, and these will have a bearing on the commitments it makes to the UK.

The EU-Japan FTA, for example, includes most favoured nation (MFN) clauses specifying that if the EU were to liberalise its services trade with another country more than it has done with Japan, then the EU would have to grant Japanese services exporters the same treatment.13 This can be thought of as a ‘we get whatever you give anyone else’ clause and variations of it exist in many of the EU’s FTAs, including with Canada, Korea and the Caribbean countries that signed the EU-CARIFORUM deal.

However, while the constraints are real, the practical implications of such provisions should not be overstated. There are caveats to take into account.

For example, the EU has a reservation specifying that the MFN clause does not apply at all if the Union enters into a sufficiently deep relationship with a third country.14 This reservation means that the EU’s agreements with Switzerland, its Stabilisation and Association Agreements with countries seeking to join the EU, the Association Agreements with Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova, and the EEA agreement are not caught by the MFN clause. Additionally, the MFN clause in the EU-Japan agreement does not apply when it comes to existing or future measures “providing for recognition of qualifications, licences or prudential measures” (meaning, for example, that if the EU recognises a qualification granted in a different country as equivalent to its own, it doesn’t automatically have to do the same for Japan).

On financial services equivalence, Barnier has repeatedly stressed that the general EU equivalence regime that is open to the rest of the world will also suffice for the UK. In July 2018, he asked the European American Chamber of Commerce in New York, “Why would this equivalence system, which works well, including for the US industry, not work for the UK?”15

One of the issues with the UK’s proposal for an enhanced equivalence regime for financial services is that, simply speaking, the EU’s third country equivalence regime is, theoretically, open to all countries that meet the qualification criteria, as with the EU’s GATS commitments.16 Expanding the scope of equivalence simply to accommodate the UK would require a broader internal discussion of the EU’s offer to the rest of the world. But again, the legal consequences of the EU’s commitments under GATS should not be overstated. If the EU did decide to go further with the UK, it could probably find a justification for doing so.

Finally, there is the issue of how the EU approaches audiovisual services, an aggressive interest of the UK. Historically, the EU has refused to include FTA provisions liberalising the trade in audiovisual services. While the EU could choose to make an exception in the case of the UK, it probably will not.

Reading between the lines, the EU may be prepared to go further than ever before on mode 3 (establishment), mode 4 (temporary movement) and mutual recognition of qualifications. However, there is little reason to think that, when it comes to mode 1 (cross-border provision) and attendant issues like licensing and comprehensive acceptance of the UK’s regulatory regime as equivalent to its own, the EU will be prepared to go much further than it has with existing third country partners. Additionally, questions remain over mode 4, and the continued movement of people in general, due to Theresa May’s insistence on ending free movement.

The EU’s approach of rolling out the red carpet for establishment, while erecting barriers to cross-border activity, can be viewed in two ways. Either it is the only route available, taking into account the UK’s desire to make its own rules and restrict the movement of people, or it is a ploy to draw more economic activity (and jobs and tax revenue) into the EU-27. In reality it is largely the former, but the latter is a happy by-product that some member-states have been keen to capitalise on. Regardless of intent, new restrictions on the cross-border supply of services will lead to a fall in the UK’s services exports to the EU.

Quantifying the impact of leaving the single market on services trade

Monique Ebell, in a paper for the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, estimates that exiting the single market would result in a 61 per cent decrease in UK-EU services trade. This translates to a 26 per cent fall in total UK services trade. She uses a gravity model to assess the aggregate impact on services trade, and concludes that new FTAs will do nothing to offset the losses.17 Her modelling suggests that leaving the single market will lead to a lot of services production leaving the UK – either to be taken by EU competitors or as a result of UK domiciled firms migrating to the EU. We seek to test and build upon this conclusion, using a different approach that allows us to differentiate impact by sector, to the best of our ability (services data is notoriously patchy).

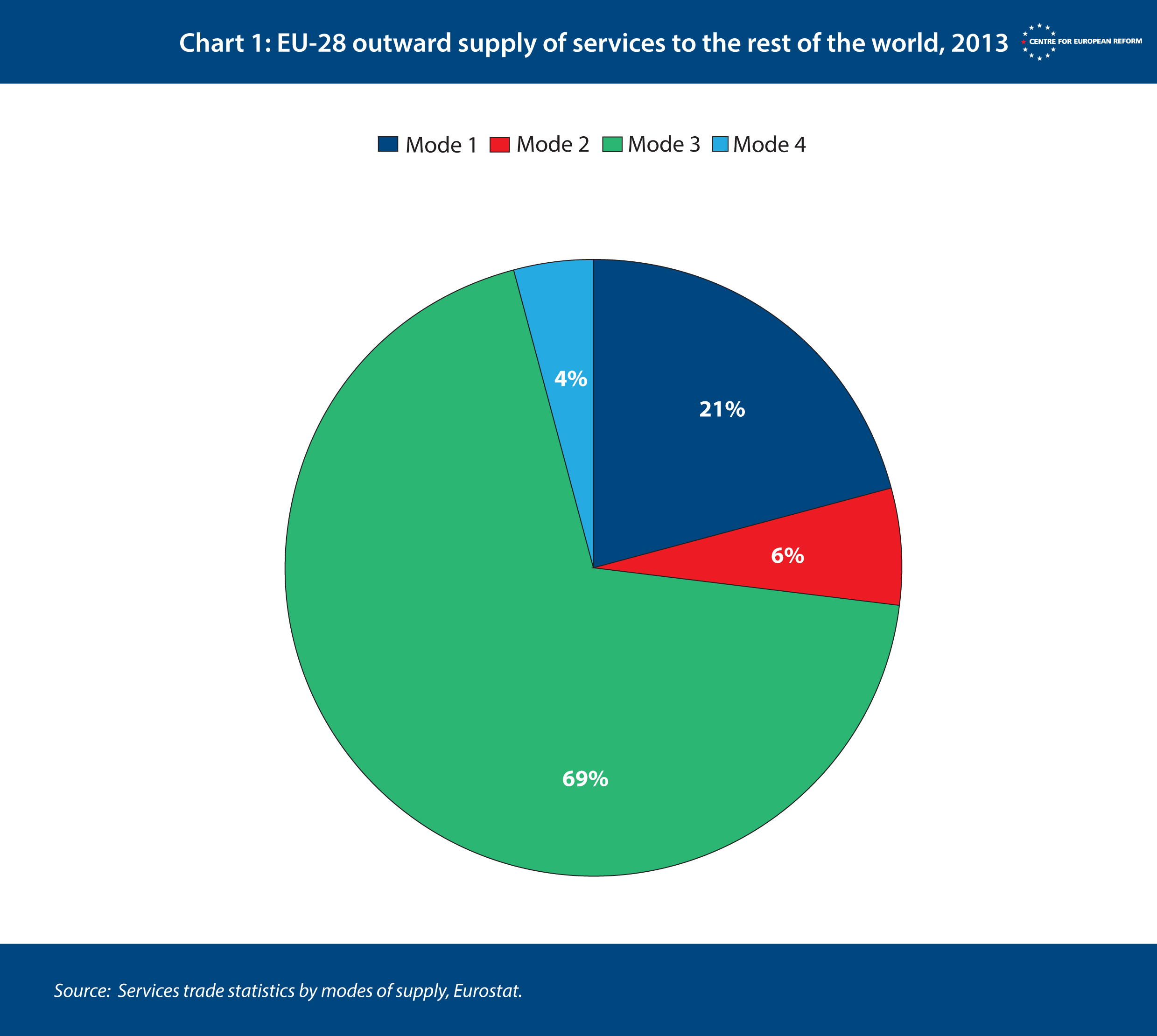

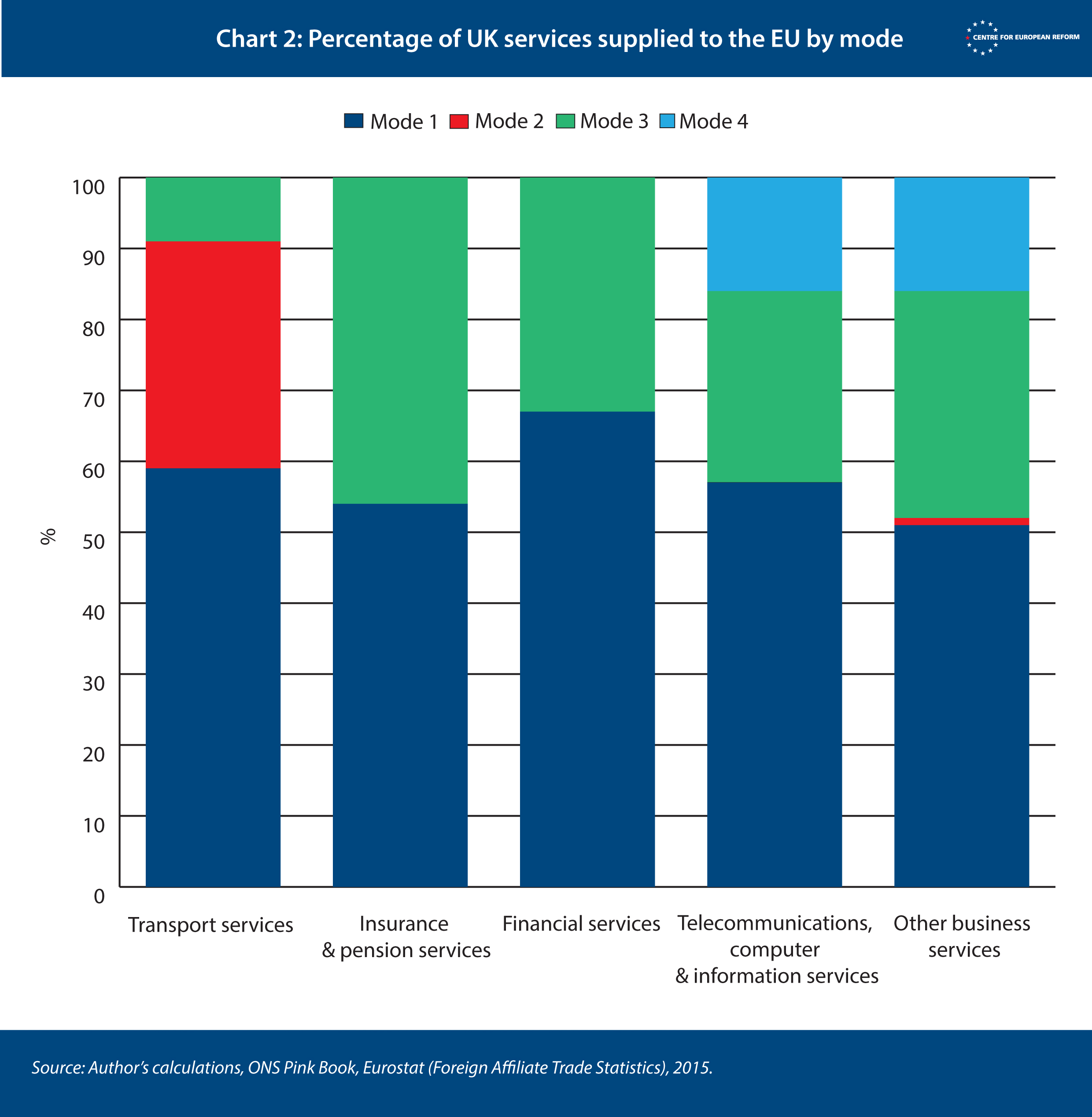

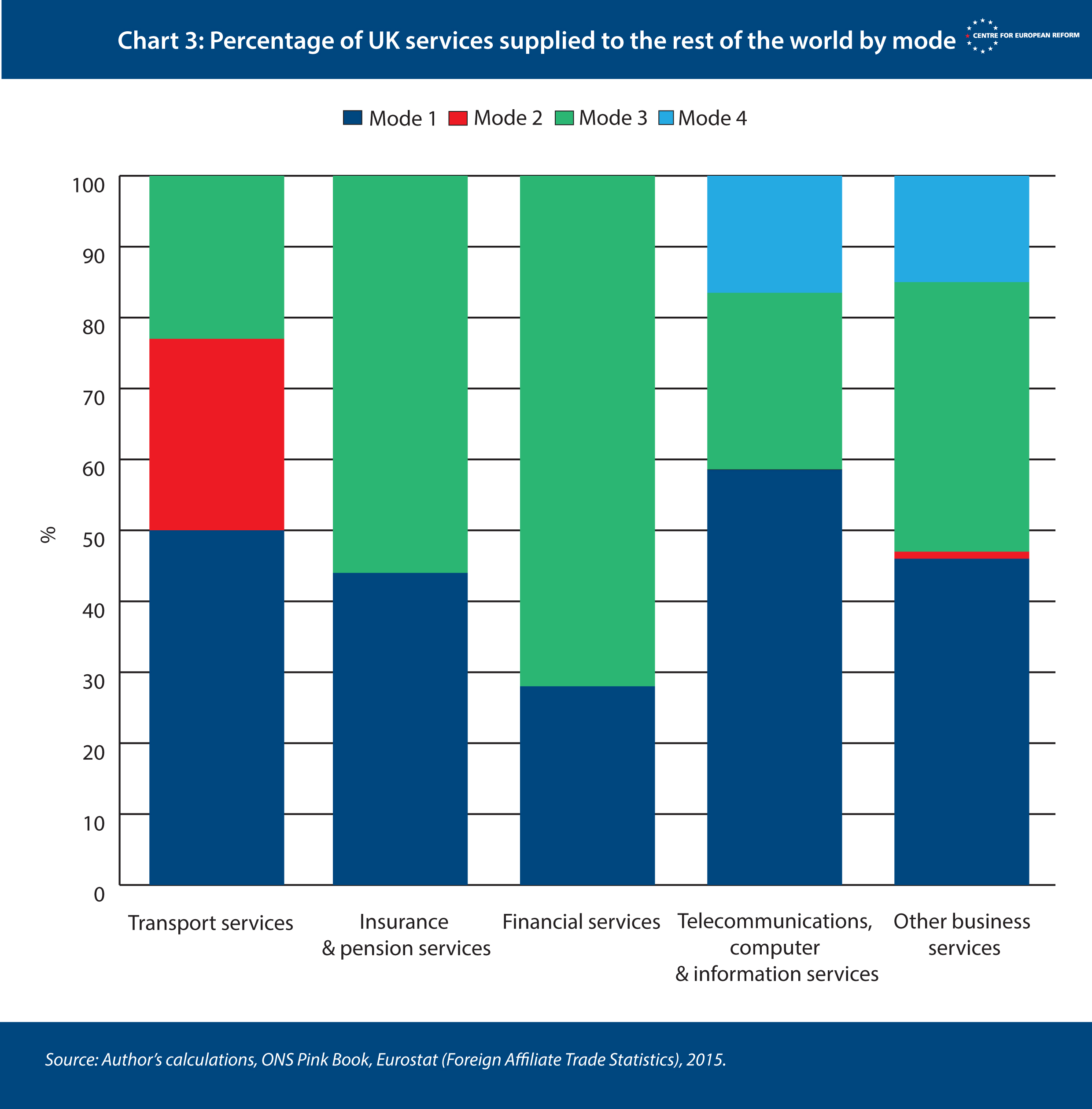

Drawing on the work of Eurostat, we have first mapped out the existing composition of UK services supplied to the EU, by mode, in relevant sectors with available data: transport; insurance and pensions; financial services; telecommunications, computer and information services; and other business services (see Chart 2). We can see that cross-border trade (mode 1) features prominently, especially in financial services.

This is in contrast to the UK’s trade with the rest of the world, excluding the EU, where mode 3 – supply through establishment in the consumer’s country – plays a bigger role.

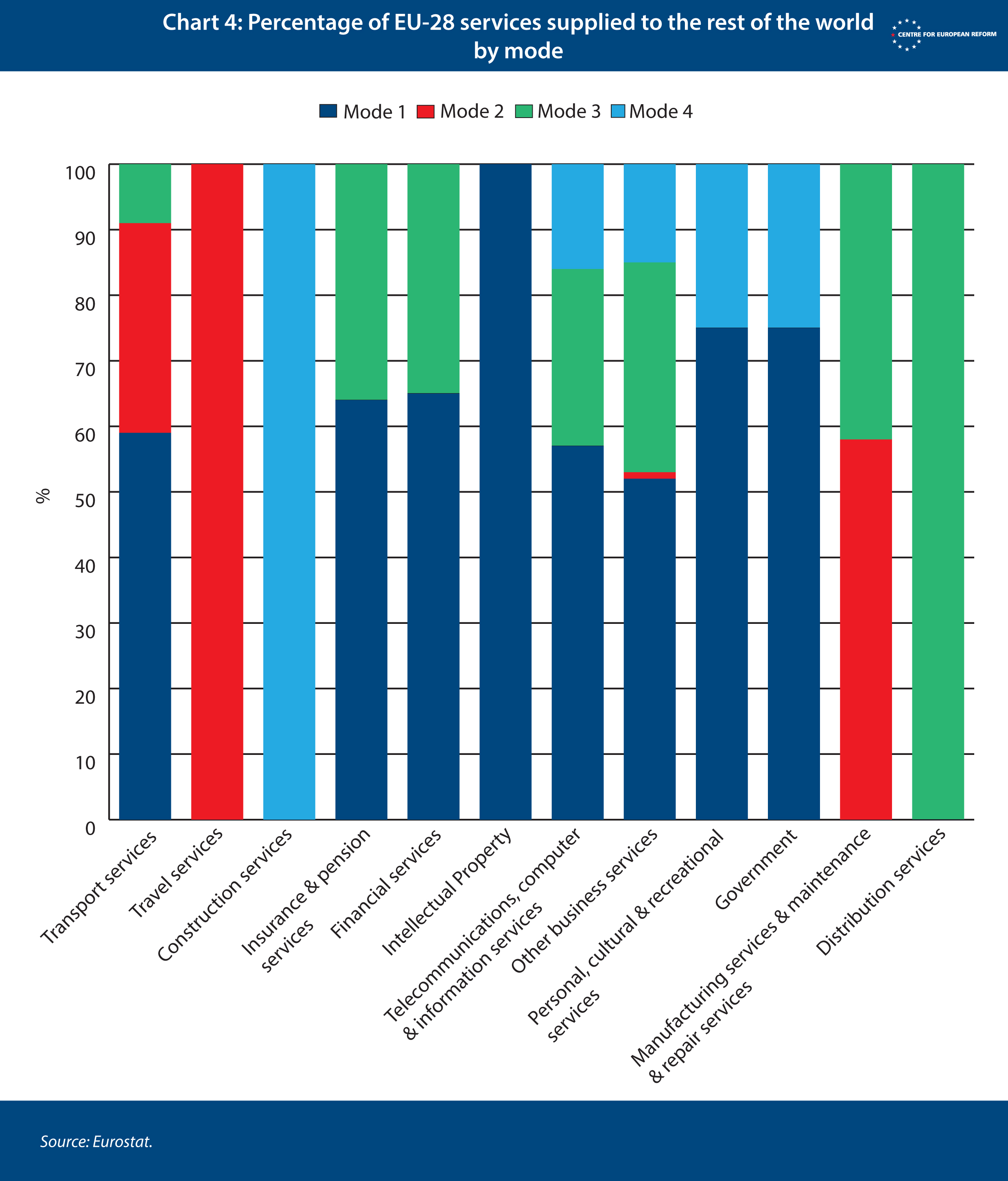

This is also true of EU trade with the rest of the world, where mode 3 is the dominant mode of supply (Chart 4).

If the UK leaves the single market, an FTA relationship will place big constraints on mode 1 and mode 4. It is reasonable to expect the composition of UK services exports to the EU to shift in profile to that of the UK’s trade with the rest of the world. That trade is largely conducted under the EU’s third country provisions, and, as discussed previously, the distinction between an FTA and GATS is minimal.

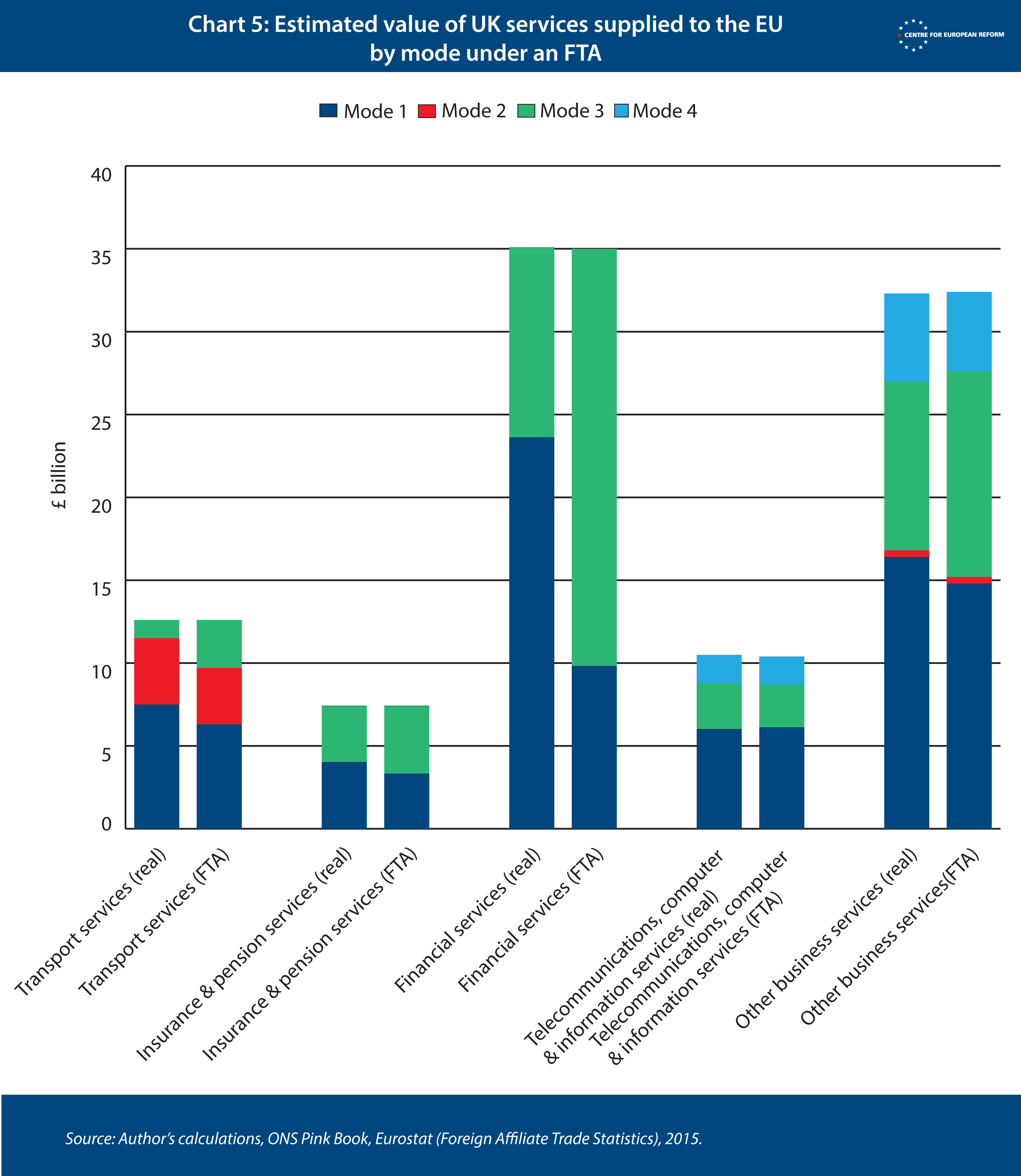

Chart 5 shows services supplied to the EU by value alongside an estimate of the composition of UK services that would be supplied to the EU under an FTA. That estimate is the value of services supplied to the EU by mode, if the composition matched those sold to the rest of the world.

We can see that exports (inclusive of modes 1, 2 and 4)18 to the EU of financial services would be around 60 per cent lower were the composition of UK exports to the EU to match UK exports to the rest of the world. Cross-border exports of insurance and pension services would be one-fifth lower. Business services would be 10 per cent lower. Cross-border transport services would be 15 per cent lower. However, telecommunication services remain much the same, increasing by three per cent, because telecoms markets remain largely national, even within the EU.

Business services will suffer less than financial and insurance services because of the nature of the sector itself, where face-to-face contact is often a necessity. Many of the UK’s big professional services firms already operate out of entities established within the member-state they are selling to. Business services is also a broad category, including a mix of regulated and less-regulated services. Mode 1 restrictions will weigh more heavily on some industries than others.

Our estimates are only a rough approximation. Other factors may come into play, including distance (being in the same or similar time zone as a customer in another country makes servicing them from your home location easier) and longstanding client-customer relationships. The percentage change should also be understood as a long-term shift and not something that would happen immediately. One would also expect to see an overall fall in total services provided across all modes, as not all lost cross-border supply would be replaced by mode 3. Even accounting for these caveats, a shift seems inevitable in the face of significant constraints on cross-border services trade with the EU after Brexit, and our findings are broadly consistent with those of Monique Ebell.

As well as denting the UK trade balance, such a big shift in the location of activity would mean falling tax revenue and investment from the UK’s traded services sector, as money that would otherwise be spent and earned within the UK moves to the EU. On the corporate taxation side, much is dependent on where any profit is booked, but it is reasonable to expect that a shift in investment and incorporation elsewhere will lead to jobs, and subsequently income tax, following.

Conclusion

If the UK is to follow through with its plan to leave the single market, then services trade with the EU will be more difficult than now. It is certainly possible for the EU to give more services commitments to the UK, compared to existing third country models, in certain areas such as mutual recognition of qualifications, right to establishment and the temporary movement of natural persons. But it is inevitable that new barriers will arise, particularly when it comes to cross-border trade. Here, where many of the barriers are regulatory, a sweetheart services deal for the UK would also require the EU fundamentally to change its approach vis-à-vis other third countries.

These barriers will lead to a change in the way UK providers service their EU-27 clients. If our estimates are accurate, the likely future relationship will have a bigger impact on some services sectors, such as financial services, than others, such as professional business services. And some ways to mitigate the impact remain in the UK’s gift. For example, an ambitious relationship with regard to the temporary movement of natural persons is possible, but it requires the UK to accept a deep, and probably EU-specific, labour mobility regime.

While the UK has been accused by some of ignoring services in the Brexit negotiations, it is more that it has come to terms with the inevitable consequences of its decision to leave the single market. Over time, the EU’s approach to third country access to its services market will evolve, for better or worse. But for now there is little reason to think it will change its approach drastically in order to accommodate a country on its way out of the club.

2: UK Government, ‘The future relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union’, July 17th 2018.

3: There is also a fifth mode of supply, so-called services in a box (the services value-added embodied in exported goods). Mode 5 will not be a focus of this policy brief because, as a concept, it is still in its infancy, and an adequate assessment would require an in-depth assessment of potential future tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade in goods, their impact, and the ramifications for dependent services providers – a subject which is deserving of its own paper.

4: World Trade Organization, General Agreement on Trade in Services: Article II, XVI and XVII.

5: World Trade Organization, General Agreement on Trade in Services: Annex on financial services, 2a.

6: Michelle Egan, ‘Single markets: Economic integration in Europe and the United States’, Chapter 7, 2015.

7: Agreement between the European Union and Japan for an Economic Partnership, Chapter 8, Trade in Services Investment Liberalisation and Electronic Commerce (EU/JP/en 173); Annex 8-A, Regulatory Cooperation on Financial Regulation (EU/JP/Annex 8-A/en 1); Annex I, Reservations for Existing Measures, Schedule of the European Union (EU/JP/Annex 8-B-I/en 1); Annex II, Reservations for Future Measures, Schedule of the European Union (EU/JP/Annex 8-B-II/en 1); Annex IV, Contractual Service Suppliers and Independent Professionals, Schedules of the European Union (EU/JP/Annex 8-B-IV/en 1).

8: One notable exception exists: while a UK lawyer has the right to represent a client in an EU-27 national court, they must be introduced by a local lawyer

9: Agreement Between the European Union and Japan for an Economic Partnership, Annex 8-A, Regulatory Co-operation on Financial Regulation (EU/JP/Annex 8-A/en 1).

10: Bar Council Brexit Working Group, ‘Brexit Paper 1: Access to the Legal Services Market post-Brexit’, The Brexit Papers, June 2017: Annex 1.

11: UK Government, ‘The future relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union’, July 17th 2018.

12: European Commission, ‘Speech by Michel Barnier at Hannover Messe’, April 23rd 2018.

13: Agreement Between the European Union and Japan for an Economic Partnership, Article 8.9, Most-favoured-nation treatment (EU/JP/en 191); Article 8.17, Most-favoured-nation treatment (EU/JP/en 207).

14: Agreement Between the European Union and Japan for an Economic Partnership, Reservations for future measures (EU/JP/Annex 8-B-II/en 25).

15: European Commission, ‘Speech by Michel Barnier at the European American Chamber of Commerce’, July 10th 2018.

16: GATS Article VII and paragraph 3 of its Annex on Financial Services hold that in situations where equivalence in the area of licensing and certification is afforded autonomously the EU “shall afford adequate opportunity for any other [WTO] Member to demonstrate that education, experience, licences, or certifications obtained or requirements met in that other Member’s territory should be recognised” also. In the case of it autonomously recognising prudential measures “it shall afford adequate opportunity for any other Member to demonstrate that such circumstances exist”.

17: Monique Ebell, ‘Will new trade deals soften the blow of hard Brexit?’, National Institute of Economic and Social Research, January 2017.

18: In the ONS Pink Book, modes 1, 2 and 4 are accounted for as exports, while mode 3 is not.

Sam Lowe, senior research fellow, Centre for European Reform, December 2018

View press release

Download full publication

Comments